Is the Dutch pension system still shining?

The Dutch pension system has been in the top 10 of the Natixis Global Retirement Index for many years and, according to the Mercer Global Pension Index, even ranks second in the world (2021) after Iceland as the best-scoring pension income system. More than any other OECD country, the total assets of the Dutch pension funds amount to 191% of GDP. Numerous examples testify to the robustness of the Dutch pension system.

However, this rosy future of the pension system in the Netherlands is not guaranteed. Legislative and policy changes in the pension system (Rijksoverheid) address many issues that test the future of our pension system. And this is important: framing possible (but also difficult to predict) developments in the area of labour migration or the future degree and capacity of automated technologies are essential to make our pension system future-proof.

What we do know for sure is that the number of young people in comparison to older people will decrease, as a result of which an increasingly smaller group of workers will be available to finance the continuous AOW - short for Algemene Ouderdomswet, the National Old Age Pensions Act system (CBS). In addition, an ever-increasing life expectancy, combined with historically low-interest rates, creates an uncertain picture regarding the support base of pension funds (PWC).

In the renewed playing field, we can assume that Dutch National Bank, the central government, pension participants, pension funds, and associated pension investors are taking on new roles and responsibilities. For this reason, we explore in 'helicopter view' the underlying causes and consequences of these developments for asset management.

The effect of an ageing population is unmistakable when we look at the number of people entitled to a pension and the number of people employed. The CBS reports that in 2030 there are expected to be some 4.2 million people aged 65 and over in the Netherlands (CBS). This means that out of an expected population of 18 million, almost a quarter (23%) of the people will be over 65.

But what does this say concretely about the future of pension administration? After all, the ageing of the population is also evidence of the increasing possibility of 'healthy ageing': increasing the capacity to work longer.

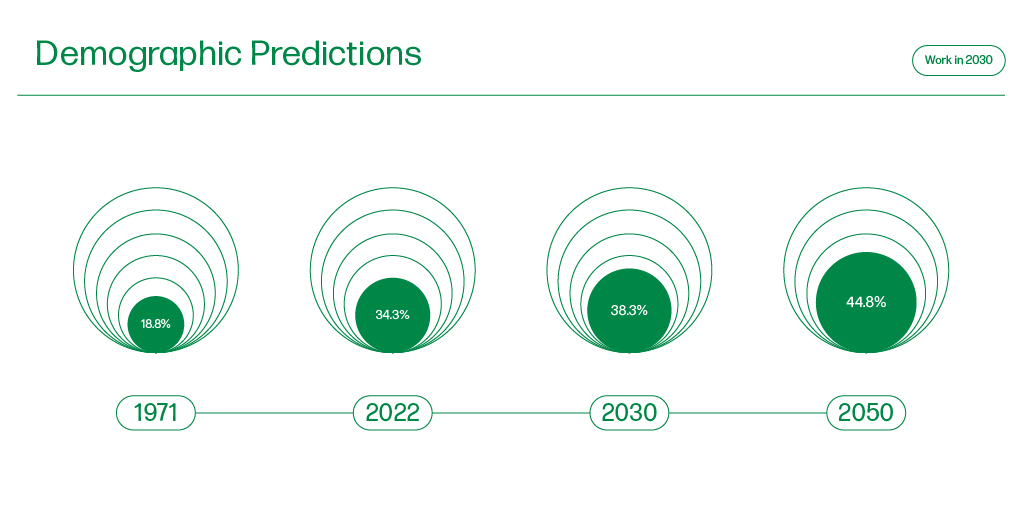

To illustrate this demographic development, it is essential to quote the effective old-age dependency ratio. This demographic indicator represents the number of people 65 and older (referred to as non-working) divided by the number of people between 15 and 65 (referred to as working). For the 2030 demographic projections, this predicted ratio (38.3% in 2030) shows that there will be about 40 non-working older people against about 100 working ones. Putting this into a more extensive time perspective, the ratio was 18.8% in 1971, is currently 34.3% (2022) and will grow steadily to 44.8% in 2050 (Eurostat).

This trend will likely continue in the longer term - what we call a 'demographic trap' (NPOKennis). The effects on the non-working population are enormous. In a nutshell, younger workers will have to shoulder more of the burden and thus reduce their purchasing power. This, in turn, has an inhibiting effect on economic growth, which has an inhibiting impact on having children. On average, future senior citizens have fewer children than previous generations - the baby boomers and later generations (Rabobank). This leads to the creation of a trap.

In summary, we see the following scenario developing: pension payments will continue for extended periods, and an ever-shrinking group of working people will have to bear the state pension burden. This raises questions about the level of benefits: can pension funds still guarantee the agreed pension? Is it at all realistic to ensure working people a lifelong pension? Is it solidarity to tax one generation more to secure the pension benefits of another? Reason enough for the development of the new pension system.

Besides the fact that the Dutch population is drastically decreasing, which will influence the input and implementation of pensions, we also see changes in the area of financial returns. In Europe, we see a flattening increase in labour productivity, and we compete with ever closer international markets. Geopolitical uncertainty (particularly the invasion of Ukraine) and the COVID-19 crisis are causing sky-high inflation, in addition to which the return on shares and investments is historically low (PWC).

In addition, the interest rate on government bonds has fallen sharply (CPB), and experts expect this to continue for a long time. In short, this puts a question mark over our current pension ambitions. What future return can pension funds expect at all? How much higher will premiums have to become? What do we advise the working generation if saving for retirement is also affected by low returns?

In short, todays (and near future) economic and demographic developments are changing the playing field. Regardless of which scenario will emerge or which questions and answers will prove crucial, pension funds can already start thinking now about how to create new forms of value. What we know: in addition to being more demanding in terms of transparency and communication, the future generation of non-working people and the current generation of working people are more adept at using the latest technology to their advantage than ever before (PWC).

Forecast of 18 million inhabitants in 2029, 2018, CBS, published by CBS, https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2018/51/forecast-18-million-inhabitants-in-2029

The pension system in the Netherlands, 2022, ADT, published by ADT, https://www.adtsolution.com/post/the-pension-system-in-the-netherlands

Pension agreement: a more transparent and personal system, 2022, Rijksoverheid (central government), published by Rijksoverheid, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/pensioen/toekomst-pensioenstelsel

Pension 2025: Scenarios for the future of the pension sector, n.a., Wim Koeleman et al, published by PWC, https://www.pwc.nl/nl/assets/documents/pwc-pensioenvisie-2025.pdf

Projected old-age dependency ratio, 2021, Eurostat, published by the European Commission, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=tps00200&lang=en

Is aging a problem?, n.a., NPOKennis (NPOknowledge), published by NPO, https://npokennis.nl/longread/7520/is-de-vergrijzing-een-probleem

Looking ahead tot he aging population and informal care: who is the informal caregiver of the future?, 2016, Leontine Treur, published by RaboResearch, https://economie.rabobank.com/publicaties/2016/januari/vooruitblik-vergrijzing-en-mantelzorg-wie-is-de-mantelzorger-van-de-toekomst/

The pension system of the future, n.a., DNB, published by DNB, https://www.dnb.nl/actuele-economische-vraagstukken/pensioen/het-pensioenstelsel-straks/

European Union Productivity, n.a., TradingEconomics, published by TradingEconomics, https://tradingeconomics.com/about-te.aspx

Low interest rates and the future of pensions, 2020, Nicoleta Ciurila et al., published by Netspar and Centraal Plan Bureau, https://www.cpb.nl/sites/default/files/omnidownload/CPB-Netspar-Policy Brief-Lage-rente-en-de-toekomst-van-pensioenen.pdf